From the Center for Community Progress:

REGISTRATION IS OPEN FOR OCTOBER’S RECLAIMING VACANT PROPERTIES CONFERENCE IN CLEVELAND!

Community Progress is pleased this year to partner with Neighborhood Progress, Inc. to bring you Reclaiming Vacant Properties: the Intersection of Sustainability, Revitalization, and Policy Reform. Join with us, and hundreds of your peers from communities across the country, to learn about the policies, tools, and strategies to catalyze long-term, sustainable revitalization. Share your experiences and insights, and become a part of the only national network focused on building the knowledge, leadership, and momentum to reclaim vacant and abandoned properties to foster thriving neighborhoods.

This engaging conference offers you three days of opportunities to build the skills and relationships to transform your communities:

- Pre-conference training seminars on key strategies, including land banking, re-imagining older industrial cities, data and research, selling houses in weak markets, and taking nuisance abatement to scale.

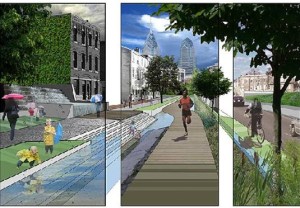

- Mobile workshops showcasing some of Cleveland’s successes, including adaptive reuse, community visioning, and legal tools in Slavic Village, historic preservation and brownfield revitalization in Detroit Shoreway, urban agriculture and green building throughout the city, and transit oriented development along the Euclid Corridor.

- 35 interactive breakout sessions covering the full range of issues related to revitalization, including assessing tax incentives, accessing REOs and other foreclosure innovations, state and federal policy, temporary uses on vacant land, creative financing, decision making for site reuse, municipal code enforcement, and much more.

- Plenaries highlighting innovative leadership and a keynote by Alex Kotlowitz (award-winning journalist and best-selling author.)

- Networking opportunities allowing you time to exchange ideas with and get to know peers.

- A new Poster Session designed so you can talk directly with even more experts.

We look forward to seeing you in October for this unique conference! Visit the conference web site to download the program and register.

A few additional notes about the conference:

- One more opportunity to present: There is still an opportunity to participate as a presenter through the Poster Session. The Poster Session will offer conference participants one more way to hear about interesting case studies, research efforts, or projects. Proposals are due July 15th so don’t delay. If you already submitted an idea for a poster through the program RFP, you do not need to resubmit. Visit the program page on the web site to find out the details.

- Scholarships: We hope to be able to post the application for registration scholarships soon. A limited number of scholarships will be available to nonprofit, public sector, or grassroots individuals. Watch for an update soon.